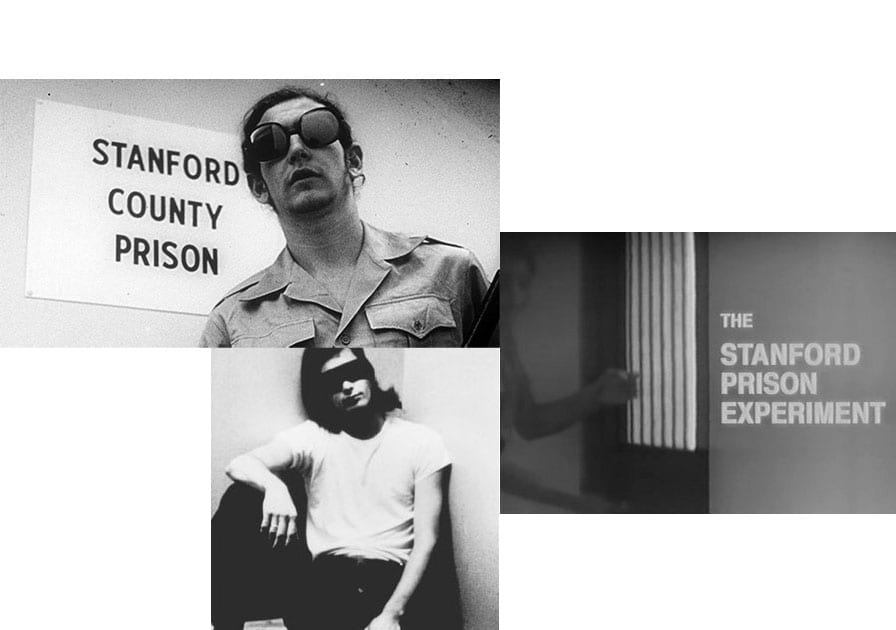

When I met for lunch with Dr. Phil Zimbardo, the former president of the American Psychological Association, I knew him primarily as the mastermind behind The Stanford Prison Experiment. In the summer of 1971, Zimbardo took healthy Stanford students, gave them roles as either guards or inmates, and placed them in a makeshift prison in the basement of Stanford University. In just days, the prisoners demonstrated symptoms of depression and extreme stress and the guards had become sadistic. The experiment was stopped early. The lesson? As W. Edwards Deming wrote: “A bad system will defeat a good person, every time.” But is the opposite true? I asked Zimbardo, “Can you reverse the Stanford Prison Experiment?”

He answered with a thought experiment referencing the infamous Milgram experiment (where subjects showed such obedience to people in authority that they administered what they believed were fatal electric shocks to patients). Zimbardo, who by an almost unimaginable coincidence went to high school with Stanley Milgram, wondered whether we could conduct a Reverse Milgram Experiment. Could we, through a series of small wins, architect a “slow ascent into goodness, step by step”? And could such an experiment be run at a societal level?

We actually already know the answer:

Positive Tickets

For years, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) detachment in Richmond, Canada ran like any other law enforcement bureaucracy and experienced similar results: recidivism or reoffending rates ran at around 60%, and they were experiencing spiraling rates of youth crime. This forward-thinking Canadian detachment, led by a young, new superintendent, Ward Clapham, challenged the core assumptions of the policing system itself. He noticed that the vast majority of police work was reactive. He asked: “Could we design a system that encouraged people to not commit crime in the first place?” Indeed, their strategic intent was a clever play on words: “Take No Prisoners.”

Their approach was to try to catch youth doing the right things and give them a Positive Ticket. The ticket granted the recipient free entry to the movies or to a local youth center. They gave out an average of 40,000 tickets per year. That is three times the number of negative tickets over the same period. As it turns out, and unbeknownst to Clapham, that ratio (2.9 positive affects to 1 negative affect, to be precise) is called the Losada Line. It is the minimum ratio of positive to negatives that has to exist for a team to flourish. On higher-performing teams (and marriages for that matter) the ratio jumps to 5:1. But does it hold true in policing?

According to Clapham, youth recidivism was reduced from 60% to 8%. Overall crime was reduced by 40%. Youth crime was cut in half. And it cost one-tenth of the traditional judicial system.

There is power in creating a positive cycle like Clapham did. Indeed, HBR‘s The Power of Small Wins, recently explored how managers can tap into relatively minor victories to significantly increase the satisfaction and motivation of their employees. It is an observation that has been made as far back as the 1968 issue of HBR in an article by Frederick Herzberg titled, “One More Time: How Do You Motivate Employees?” (PDF). That piece has been among the most popular articles at Harvard Business Review. His research showed that the two primary motivators for people were (1.) achievement and (2.) recognition for achievement.

Very, Very Small Wins

The lesson here is to create a culture that immediately and sincerely celebrates victories. Here are three simple ways to begin:

1. Start your next staff meeting with five minutes on the question: “What has gone right since our last meeting?” Have each person acknowledge someone else’s achievement in a concrete, sincere way. Done right, this very small question can begin to shift the conversation.

2. Take two minutes every day to try to catch someone doing the right thing. It is the fastest and most positive way for the people around you to learn when they are getting it right.

3. Create a virtual community board where employees, partners and even customers can share what they are grateful for daily. Sounds idealistic? Vishen Lakhiani, CEO of Mind Valley, a new generation media and publishing company, has done just that at Gratitude Log. (Watch him explain how it works here).

These are just a few practices. But experimenting with the principle could have far-reaching consequences.

Indeed, Zimbardo is attempting a grand social experiment himself called the Heroic Imagination Project (watch his TED Talk here). The logic is that we can increase the odds of people operating with courage by teaching them the principles of heroism. The results are already fascinating.

The Stanford Prison Experiment was profound. But just imagine what would happen if we could consciously and deliberately reverse it.

Read the Original Post: Can We Reverse the Stanford Prison Experiment? – Harvard Business Review

Pingback: Can We Reverse the Stanford Prison Experiment? – Harvard Business Review by Greg McKeown « Taylor Halverson

the ted video has moved… when on ted look for Phil Zimbardo

Pingback: Reversing the 1:50 Ratio – A gut-check on values and A response to Greg McKeown « Performance. Aligned.

Greg, I agree, and after writing a response for 10 minutes, I thought it should go somewhere else (http://snipurl.com/24crgze). The net of it is that it’s not the experiment that we should reverse, but role perception, which might have something to do with what you mentioned elsewhere about people and contribution.

Best,

Pt

Really informative article.Great insights.